Isaiah 55:6-9

Psalm 145

Phillipians 1:18, 20c-24, 27

Matthew 21:12-17

“For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways My

ways,” says God. “For as the heavens extend unfathomably beyond the earth, so

are My ways far from your ways, and My thoughts from your thoughts.” These

words come to us from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah and on first glance, there

might not seem to be anything remarkable about them. Of course God’s ways are

not our ways. God is beyond our comprehension. For years, humankind has tried

to describe what God is – or what God is not – and the debate continues because

God is beyond our wildest dreams and imaginations.

But what does it mean that “God’s ways are not our ways?”

What does it mean to proclaim Christ in every way? To live life in a manner

that honors the gospel of Jesus the Christ? Well, my friends, today’s gospel

gives us a pretty good example. Because today’s gospel contains that wonderful

gospel passage where Jesus drives out the money lenders and turns over tables.

To live life in a manner that honors the Gospel, honors the Good News of Jesus

the Christ is to remember that we are called to something greater. To remember

that we are not supposed to go along with society or the status quo simply

because it is the way of things or tradition. It means recognizing that we are

called to be a new creation, a new church, a new beloved community.

I’m sure we’ve all heard many a sermon on Jesus and the

money lenders in the temple. I want to draw your attention to a detail in the

account we heard from Matthew’s gospel today. Right after we have Jesus

overturning tables and driving out the money lenders, we have Jesus welcoming

people who were blind and people with disabilities. These were individuals who,

according to tradition, should not have been allowed in the temple since they

were considered unclean, but Jesus welcomes them and heals them.

This did not make Jesus a popular person with religious

leaders and authorities. Because Jesus was going against the established order,

challenging the system, being a prophet and calling for justice. Jesus was

protesting the way things were and showing us how they ought to be.

Here’s the thing about prophets and protesters – people

often don’t like them. Prophets and protesters unsettle us. They challenge us.

They disrupt our sense of calm, our sense of stability. They do “inappropriate”

things to get the message across.

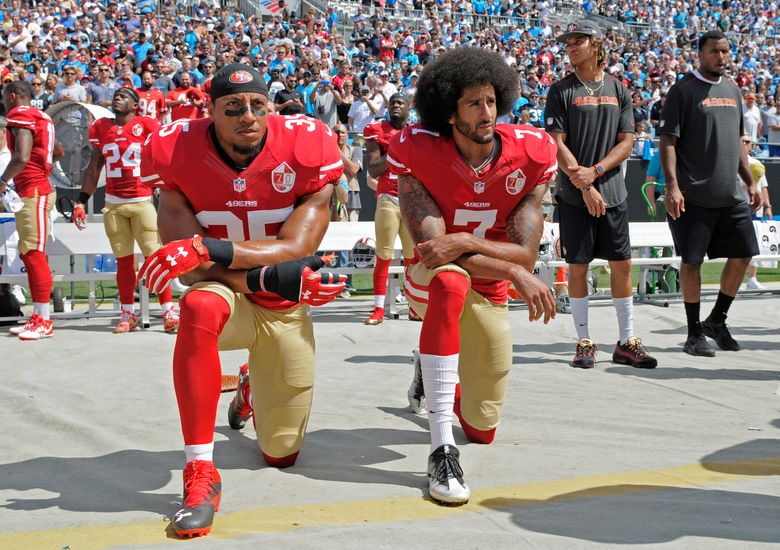

I’m not sure how many of you are football fans – but over

the last day or two, there’s been a flurry of activity and rhetoric around

Colin Kaepernick and other athletes’ decision to kneel during the national

anthem to protest racial injustice and police brutality in the U.S. The

president has called out the protesters, saying anyone who kneels during the

anthem deserves to be fired. Today, in major league sports games played nation

wide, numerous players kneeled in solidarity – defying the established order,

protesting injustice and calling for America to turn its attention to what it

doesn’t want to see – the systemic racism that pervades our society.

Last week we were fortunate enough to hear from Dr. André

Branch, president of the San Diego chapter of the NAACP and some of us will

attend their fundraising dinner in a few weeks. But how else are we working to

deconstruct the racist systems in our midst? To do the anti-racism work Jesus

calls us to means not just inviting distinguished black scholars to speak, but

to examine our own reactions to athletes of color who kneel during the anthem?

What stirs in us when we see people of color protesting? How do we respond?

People have accused Colin Kaepernick of being disrespectful

– yet what about kneeling is disrespectful? “To kneel is to show respect. To

make a statement. To humble oneself, but also to stand out from the wider

world.”[1]

We might not all agree with Kaepernick’s actions, but surely we can see that

our country is struggling with its racist past and present. And yet, many

Americans are willing to go on with their lives, ignoring anything that doesn’t

affect them personally. This might be the way of humankind, the way of American

individualism, but as Christians, we are called to something more. We are

called – and we have chosen – to follow a prophet who spoke truth to power, who

flipped tables in the temple – seemingly desecrating the most holy place, who

healed the sick and those with disabilities, who raised up the poor and the

oppressed. Remember, God’s ways are not our ways – and we should not be swept

up by nationalistic and populist rhetoric, but keep our minds and our hearts on

God. A God who is love and justice.

Over the last few days, there has been a lot of talk about

the “proper” way to protest. But to protest isn’t proper. It might be right and

just, but it isn’t always pretty and proper. It’s about shaking up the status

quo, disrupting the norm, and drawing attention to things that might otherwise

be overlooked. When Jesus flipped over the tables in the temple, it wasn’t out

of some vendetta for those individuals, but to disrupt their actions – actions

which were extorting the poor. Yet, in the midst of his outrage, Jesus takes

the time to heal those in need. Because even our anger and outrage at injustice

needs to come out of love and faith. Our actions should come out of our beliefs

that all people, regardless of race, gender, sexuality, are wonderfully made

children of God. That all people are deserving of our respect and our

unconditional love. And when the world tries to tell us otherwise, well, we

might have to flip a few tables or take the knee during the anthem.

In closing, let us join in a prayer by Mother Teresa of

Calcutta:

We pray for anyone of our acquaintance

who is personally affected by injustice.

Forgive us, God, if we unwittingly share in the conditions

or in a system that perpetuates injustice.

Show us how we can serve your children

and make your love practical by washing their feet.

who is personally affected by injustice.

Forgive us, God, if we unwittingly share in the conditions

or in a system that perpetuates injustice.

Show us how we can serve your children

and make your love practical by washing their feet.

Amen.

[1] Rev. Angela Denker, “Colin Kaepernick

and the powerful, religious act of kneeling,”

(9/24/2017)

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2017/09/24/colin-kaepernick-and-the-powerful-religious-act-of-kneeling/?utm_term=.69236121b0ab